Rocky Mountain Bicycles' Dream Factory

Photos by Justin Walker and Marcus Riga

Photos by Justin Walker and Marcus Riga

Rocky Mountain Bicycles’ headquarters, right next door to Vancouver’s famous North Shore trails, is a mountain biker’s dream world. We go behind the doors to find out how this famous company produces its bikes.

I had just entered a mountain biker’s dream world; stepping through the front door of Rocky Mountain Bicycles’ Vancouver, Canada, HQ, I was greeted by a number of smiling faces, plus more MTB porn hanging from the walls than you could ever imagine.

In the beginning

Rocky Mountain Bicycles has been around for 34 years, being founded in 1981 by Grayson Bain and some fellow riders working out of a Vancouver bike shop. Grayson and his mates were hell-bent on building bikes that were better than those available at the time, so Rocky Mountain Bicycles was born; the first model was – ironically, considering the company’s latest rig – the “Sherpa”. The company started with the ethos it still adheres to today: building bikes “we want to ride here” – as in, Vancouver’s famous North Shore. Since 1981, the brand has become synonymous with mountain biking and its many disciplines, thanks to both its bikes and its athletes (think: Wade Simmons, Andreas Hestler, Brett Tippie and Thomas Vanderham).

For many years, the company produced bikes out of its Vancouver factory, before moving frame production (like most bike brands) overseas (around 80% of the company’s bikes are still assembled in Canada, however). Even though the frames are manufactured overseas, the design, engineering and prototype testing is done in-house by a team of four engineers located at Rocky’s Vancouver HQ.

On tour

A tour of the Rocky Mountain factory is a real eye-opener for any MTBer, with the HQ and factory containing some innovative bike designing technology, a passionate team of engineers and builders, plus a fair bit of MTB history.

Game time!

Game time!When I visited the factory in mid 2014, it was this history (along with a heap of welcoming, smiling faces) that I first encountered, just after meeting Anja Koehler, Rocky’s Marketing Coordinator, who was my host for the factory tour. Hanging on the walls of the front office were several early Rocky Mountain frames, including an ultra-rare build from frame-maker Derek Bailey. Dubbed the “Bill B”, this frame is one of only two of its kind and has some cool metalwork, including amazingly detailed lugs. Throughout this front area are all the engineers’ workstations, and other staffers’ desks, along with myriad bits and pieces of RM bikes. It was a couple of things on the other side of the office, however, that captured my attention: proudly displayed in one of the meeting rooms was Wade Simmons’ 2002 Red Bull Rampage trophy that he won at the original Jindabyne event. And further along, sitting innocuously in the corner, I spotted the then-unreleased carbon-fibre Rocky Mountain Thunderbolt MSL BC Edition. In short, a dream trail bike in a dream factory – if only I could’ve smuggled it out of the office and onto the plane back to Sydney with me…

Prototypes lurk inside the walls…

Prototypes lurk inside the walls…While the Thunderbolt MSL BC Edition didn’t make it into my luggage, I was more than compensated by the factory tour (and a later ride with Wade and Andreas). On the tour I could follow the progression of a bike’s life, such as the Thunderbolt, from idea to trail-shredding reality.

First things first

Brian Park is Rocky’s Content Marketing Manager and, like all RM employees, a passionate rider. Having grown up riding his old man’s mid-90s RM Fusion and being inspired by the antics of Simmons, Tippie and Vanderham, he now enjoys the dream job, promoting a highly respected MTB brand and riding some of the world’s most famous trails in BC.

When I asked Brian where the original idea for the Thunderbolt came from – an engineer or a group-focus on that market segment – he filled me in.

“Our product director, Alex, wanted to build a smashy little XC-trail bike, and then we gathered feedback and did market research to figure out what that looked like. That’s kind of how things go here; we don’t go, “oh shit, we need a short travel 27.5 bike with 120mm travel to compete with XYZ,” we get inspired by a specific use-case or market segment and then dig into the design phase.”

As Brian pointed out to me, the XC-trail bike market is growing, but there are still not too many bikes out there that stand out. The Thunderbolt does though, for a variety of reasons, all of which make the bike extremely versatile. “The Thunderbolt ticks all the boxes for us,” said Brian. “It’s sensibly light, stiff as hell, pedals like a rocketship, and is fully Di2 compatible. It has modern geometry with short, playful chainstays and an increased reach, and RIDE-9 provides geometry and suspension adjustments from trail blasting to full-on marathon racing. We’re biased for sure, but we think it’s a true contender in the category…”

Drawing up a dream

A bike doesn’t just go from idea to physical reality quickly or easily, however. As Brian explained, the development process involves a series of stages, from concept, research and design, through to the first test mule, feedback from riders/testers, a fair bit of heated discussion, loads of coffee, a second test mule build, more design input and coffee, and then a prototype, followed by final design tweaks and then the product launch. All of which is celebrated with a few cold beers. It definitely sounds a long process, but one that would be immensely rewarding for all the people involved, from designers/engineers, through to testers and marketers.

It also helps that all the engineers and product staff are keen riders and get to share plenty of trail-time with test riders such as Andreas Hestler, Thomas Vanderham and Wade Simmons. This ensures that tester feedback goes directly back to the engineers and designers, making for a streamlined, efficient development process.

The designers use 3D-modeling and FEA software to design each bike and, usually, the design team will split into smaller groups for each bike. However, this is not always the case.

“Generally it’s a product manager that’s developing geometry on aluminum test mules and gathering feedback from there, and generally one engineer will lead the work on a specific project,” explained Brian. “But, for example, D’Arcy [MTB Design Manager D’Arcy O’Connor] might be developing a bike’s suspension kinematics while Joe works on its tube shapes and Lyle works on fine-tuning the link and hardware tolerances. Bike design is pretty collaborative and involved.”

The designers’ other asset is the 3D printer, which is used to produce 1:1 scale versions of the bike frame. This allows the team to see the bike in proper scale and format, allowing them to work out fine frame details, such as clearances and cable routing.

Behind the back door

It was as I entered the work factory with Anja that I spotted the evidence of one of the key stages in Brian’s explanation of the design process: a beautiful espresso machine, featuring a hand-machined tamper that was made in-house – it even had a custom-made piggy bank that employees drop money in to fund the constant consumption of caffeine.

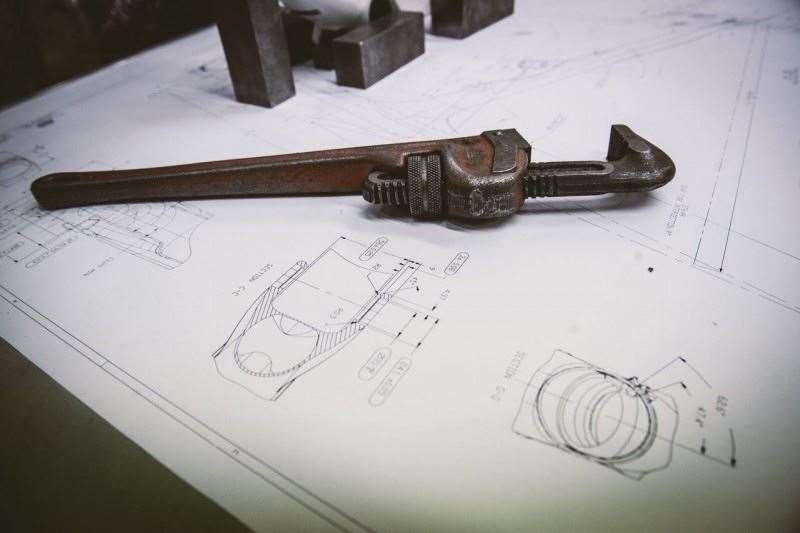

Moving further in to the fabrication section of the factory was like walking into a different world; one in which any budding bike engineer would love to reside. A CNC machine sat beside a frame-stress testing rig, a wheel-deflection test rig was nearby, a lathe sat in another space, bike frames of various shapes, sizes and of varying materials (plastic and alloy) were, literally, hanging around or sitting atop design papers; old – and famous – Rocky frames hung from the wall; while a number of employees moved around the floor space that was left. It is out here that the grunt-work of test mule frame fabrication takes place. And being able to make any part needed, quickly, is the big advantage of doing your own building and fabrication.

In short, it’s awesome.

The order in which each bike is tested on these rigs is: “deflection, stress, then overload testing,” said Brian. “We love breaking stuff”.

And it is this rigorous testing procedure, via the numerous test machines – that grabs the eye – especially the one used to test frame fatigue. On my visit, a prototype carbon-fibre Thunderbolt frame was attached to the fatigue tester, a rig that tests the frame for the maximum weight it can withstand before cracking. It’s pretty amazing how much flex/movement this machine can induce in the frame. I moved along to the next test rig where Billy, a long-time RM employee, joined Anja. They explained that this rig replicates the pedalling process, and how many pedalling “cycles” (measured in time and pedal rate) the frame can withstand. The frame in this rig had already withstood 100,000 cycles. Pretty impressive stuff, as were the raw, rough-finish alloy frames I saw lying about – these are key to design success, being the test mules that are, Brian said, used for suspension calibration and frame geometry. And this is, again, where a fully-fledged factory in-house offers advantages.

“Testing aluminum mules is just for suspension performance and geometry, so we generally don’t need a long time to draw informed conclusions,” Brian said. “One of our biggest competitive advantages is having a full fabrication and prototyping shop at our fingertips, so we’re able to make changes and try a variety of things in a short period of time.”

It’s all in the timing

There’s no massive rush in regards to developing a new bike model at ROM – the average development phase is 18 months – but Brian explained the carbon Thunderbolt was a “crazy-fast” timeline, but this was mainly due to having the solid base already in place with the alloy variant.

Brian mentioned that the product team is totally focused on making sure things are working as they envisage before signing off on the next step in the development. And, he said, there’s always room for future improvements and innovative developments. A perfect example of this is Thunderbolt and its alloy incarnation (released 12 months previous to the carbon-fibre rigs) not including Rocky Mountain’s excellent RIDE-9 system, which is found on the carbon-fibre versions.

“Not including RIDE-9 on the alloy Thunderbolt wasn’t a time-related decision, we left it off to focus on simplicity and save a little weight,” Brian said.

It was when RM staffers found themselves tackling gnarlier terrain on the alloy models that they knew the carbon version would benefit hugely from RIDE-9. (And for all those alloy-frame fans, RM has not discounted adding RIDE-9 to the metal models at some stage.)

Always looking forward

The other design feature on the carbon Thunderbolts – that actually came about as a result of designers working on an as-yet unannounced bike – is the main pivot’s Pipelock collet system, which ups the rigidity of the Thunderbolt significantly. This, and the use of the also-new BC2 pivots in the carbon Thunderbolt, only 12 months after the release of the alloy version, prove the benefit of having designers, product managers, testers and fabricators, not to mention the sweetest of singletrack test locations in the nearby North Shore, very close at hand. Something Brian reiterated when I asked him of the importance of an in-house “bike laboratory”.

“No question that our Development Centre is critical to our design process and our identity as a company, especially with it being minutes away from the great testing terrain that we have here on the North Shore. It’s awesome for our tight-knit team to be able to collaborate and be involved in such a short, agile feedback loop – whether it’s getting a custom link machined to try a different curve out, or having Al the master fabricator do a complete ground-up test mule.”

For me, an in-awe visitor to this hallowed turf, that message was what stayed in my head after I left. Besides the brilliant bike design and fabrication work that goes on here, the fact that everyone at Rocky Mountain HQ is both proud and passionate about the brand really shone through. Knowing just how much thought, work and countless hours of testing goes into building the rig you pay for in your local bike shop makes that initial outlay a sound investment.