Trek Suspension R&D - Factory Tour Part 1

Wil Barret visited Trek's suspension R&D facility to get the low down of how Trek choose to optimise the design and of their suspension.

Back at the start of June this year, I took a trip over to the US to visit a handful of bike companies on behalf of AMB Magazine. One of the companies I had the opportunity to catch up with was Trek Bikes. But instead of flying halfway around the country to Wisconsin to visit the company headquarters and carbon manufacturing facility, I jumped in a hire car at LAX airport, and drove an hour up the road to Santa Clarita in California. Being the global brand that they are, Trek have multiple facilities located across the States and all around the world that carry out R&D for their extensive line of road bikes, mountain bikes, commuters, as well as the Bontrager parts and accessory range. And so the reason I was deviating off the I5 towards Santa Clarita then? Because this unassuming building located at the back of an industrial complex is the home of the Trek Suspension Lab.

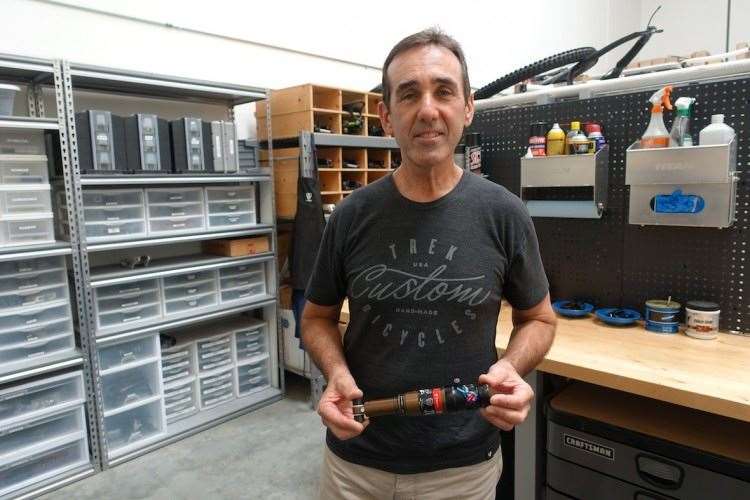

June is a busy time of year in the bike world, with new model bikes and components being released left, right, and centre (in fact, just two weeks after I got back from my US trip, Trek released the brand new Top Fuel, Procaliber and Fuel EX models). Despite having a very busy schedule filled up with prototype testing and international product launches, I was fortunately able to tee up a meeting with Trek’s Director of Suspension Development, Jose Gonzalez. Thankfully for me, Jose was more than happy to clear his Friday morning timetable in order to show me around their workshop and talk me through the role that they play in the development of new Trek mountain bike technology.

As Director of Suspension Development at Trek Bikes, Jose Gonzalez has helped develop a number of unique suspension technologies. You might also know him as the Father of DRCV.

As Director of Suspension Development at Trek Bikes, Jose Gonzalez has helped develop a number of unique suspension technologies. You might also know him as the Father of DRCV.Known amongst the mountain bike industry as a bonafide suspension guru, Gonzalez actually started his career working with Kawasaki motorbikes back in the day. Gonzalez had always been an avid cyclist himself however, so when an opportunity arose for him to apply his experience and expertise from motocross racing to the mountain bike world, he took up a job opportunity to work for Answer/Manitou. Gonzalez worked with Manitou for over a decade, where he saw through the evolution of their mountain bike forks and rear shocks from the very early days elastomers and skinny stanchions, to the sophisticated TPC dampers and modern Reverse Arch chassis.

In 2006, Gonzalez was headhunted by Trek to establish their brand new Suspension Lab. This was part of a wider movement at the time for Trek Bikes, which coincided with a number of specific investments and the hiring of fresh talent including Dylan Howes (Director of MTB Frame Technology), to help spearhead the progression of the brands off-road range. Trek was always been well known for their road bikes, but they wanted to offer class-leading mountain bikes too. “That was kind of the investment we made almost 10 years ago now, to become a leader in mountain bikes”, Gonzalez explained to me during my visit. And looking back to that time nearly a decade ago, it’s easy to see the transition that Trek underwent in their product line that followed this conscious decision by the company. Models such as the Slash and carbon Session 9.9, along with the latest generation Fuel EX and Remedy models have all been a direct result of this new invigoration of the company’s off-road team. Other, more specific technological fruits from this labour include the ABP suspension design, the Hybrid Air system used in the Fox 40 fork on the Session, and more recently, the RE:aktiv damper. That said, it’s surely the DRCV rear shock that has been the most significant innovation to come from Trek’s Suspension Lab.

You’re met with little fanfare and glamour when walking into the Suspension Lab. It’s a relatively small building that has a simple but clean layout, with multiple work stations used for specific tasks such as shock tuning and bike building. Sitting proudly on display in the front lobby is one of the first prototypes of the new generation Trek Remedy, which was used to evaluate the ABP and Full Floater suspension design, amongst other aspects too. Trek have surely built and marketed much flashier and higher-performance rigs since, but this raw aluminium prototype is the perfect symbol to represents all of those technological innovations that have laid the foundations for Trek’s contemporary full suspension line.

Despite my grandiose expectations of what the Suspension Lab might look like, the compact layout admittedly contains everything Gonzalez and his team of three need to fulfil all of the prototyping and testing in-house. There is a lot of specialist equipment in here though, and Gonzalez estimates it cost Trek around $400k USD to implement the facility. To summarise what the Suspension Lab does, they essentially work on fork and shock technologies that will help the mountain bike development team achieve the desired ride characteristics for a particular model of bike they’re working on. This could be as simple as testing and deciding on a specific custom tune for a RockShox Monarch shock on a Trek Slash. Or it could be as complex as building a fully customised damper to fit inside a Fox fork on the front of a Fuel EX. Or it might be working on a prototype dropper seatpost…

Typically the team is working on projects 2-3 model years out, so when I’m walking around the workshop, there are several curtains draped over certain things that I’m not allowed to see. That said, it’s worth remembering that this facility is purely carrying out an R&D role, so anything I do see is likely a ways from production, or may not ever enter production at all. And it is this freedom to conceptualise that is the real beauty about what Gonzalez gets to do. His team’s sole purpose is to come up with the ideas and help build the prototypes, then test the concepts both inside the lab and outside on the trail. They also work closely with partners such as Fox Racing Shox, RockShox, and Penske, both in the prototyping and testing phase to prove or disprove certain theories. Trek’s involvement with these companies early on in a product’s development is also paramount to the viability of that product seeing mass production. Gonzalez states that sometimes his team will go so far as to test a 2nd generation prototype that’s relatively close to production, but beyond that there is no need for them to be involved any further. In the case of the DRCV rear shock, once the suspension team had proven the concept, the responsibility of how to build the shock and how to package the Dual Rate Control Valve was in the hands of their manufacturing partner, which in that case was Fox. And so once Gonzalez’ team hands off a particular project to Trek’s MTB development team and their manufacturing partners, they can then return to testing and progressing other projects.

Testing the DRCV air spring as well as various iterations of shim-stack arrangements for the RE:aktiv damper. DRCV was one of the first big projects to come out of the Suspension Lab, and it was a design that Gonzalez pursued in order to address the overly progressive spring curve of air shocks at the time. DRCV creates a more active and responsive mid-stroke, which helps to flatten out the spring curve to see it behave more like a coil spring. The RockShox Debonair and Fox EVOL air sleeve designs share a very similar spring curve to DRCV, and you could say those suspension companies were inspired by Trek’s clever rear shock design…

Testing the DRCV air spring as well as various iterations of shim-stack arrangements for the RE:aktiv damper. DRCV was one of the first big projects to come out of the Suspension Lab, and it was a design that Gonzalez pursued in order to address the overly progressive spring curve of air shocks at the time. DRCV creates a more active and responsive mid-stroke, which helps to flatten out the spring curve to see it behave more like a coil spring. The RockShox Debonair and Fox EVOL air sleeve designs share a very similar spring curve to DRCV, and you could say those suspension companies were inspired by Trek’s clever rear shock design…

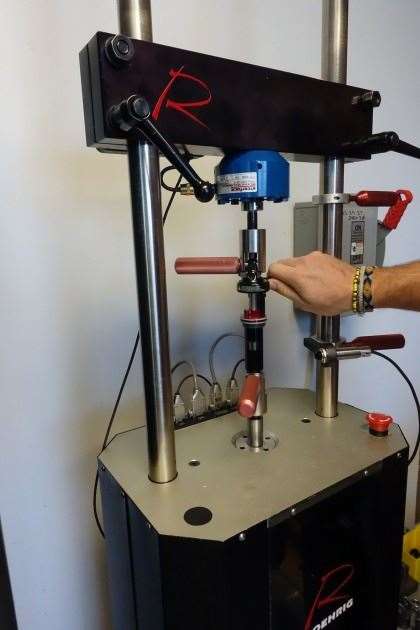

When Gonzalez first setup the Suspension Lab, the team’s very first point of call was to develop specific damper tunes for the Fox forks and shocks fitted to Trek’s mountain bikes. Trek didn’t just want to run off-the-shelf dampers for their bikes, and they were looking for a more ‘balanced’ ride quality between the front and rear of the bike, which required going more in-depth than your typical bike company does. To carry out this custom tuning effectively however, you need a very expensive piece of machinery. “It was one of the first things I did when I came to Trek was to convince them that we needed a dyno”, explains Gonzalez. “And you can imagine how that went! Asking for a machine that was 50-60 thousand dollars!”

The suspension dyno that Trek use is made by Roehrig in North Carolina. The EMA Dyno works on Electro Magnetic Actuation, which means it works similar to a speaker in the way that it converts electric current into physical movement. It allows them to fit a fork or shock, and cycle through its travel in order to test compression and rebound settings, as well as the effect of any particular damper tunes they might be working on. This particular Dyno cost around $60k USD and was custom built for Trek due to the different requirements compared to motorsport. They also had longer rods fitted that would allow them to fit a full length downhill fork. Highlighting Gonzalez’s previous motocross experience and passion for high octane motorsport, he goes on to explain that “anyone who’s anyone in motorcar racing and suspension world has one of those dyno’s. Motocross, Nascar, Indy car, Moto GP – they have this dyno.”

For Trek, this machine forms a huge part of their capability in producing class-leading product. “You can tell if a company is serious or not about suspension by asking to see their dyno. If they can’t show you their dyno, then they’re not serious about the work they do”, Gonzalez states. “You can’t do what we do without this tool. It’s a critical part really. You’re working blind otherwise, to be honest with you.” And so combined with their machine shop out back, the Roehrig EMA allows Gonzalez’ team to quickly develop and test fine-tune changes to certain damper configurations that would take them days or weeks of testing out on the trail to evaluate to the same degree.

That said, it’s refreshing to hear Gonzalez explain that as effective and efficient as it is, in-house testing isn’t the be all and end all of suspension development though. “Seat of the pants is still ultimately the final value” Gonzalez tells me, confirming that on-trail testing is still a massive part of what they do. “It doesn’t matter what machines tell you. If the rider doesn’t like it, then the rider doesn’t like it. End of story. And in talking with Penske, it’s the same for them. You know, they have simulators and all this kind of stuff, but ultimately the driver makes the final call. It’s gotta work for them, and if it doesn’t, then they can’t do their job.”

Field testing is a massive part of what Gonzalez’ team does at the Suspension Lab. Their facility houses a full workshop separate to the dyno room, which is designed to facilitate bike building and setup before hitting the local trails. The Suspension Lab also has regular visits from Trek Factory Racing team riders and sponsored athletes who help to test out new suspension products.

For Gonzalez, having his staff ride the product is far more important than anything they could be doing in front of a computer screen. “You’ve gotta stay in tune with the machine, and to do that you’ve gotta spend consistent time on it” he explains. “So we make a point to ride on a regular basis. As an example, yesterday Phil and Jason went and rode before coming to work, so they started a little later so they can head out in the morning when it’s nice and cool, because that’s the thing out here it can get really hot in the summer. Often the best time to ride during summer is 6 o’clock in the morning when its 75-80 degrees (23-26 degrees Celcius). So they know they’re fully approved to go ride at least a couple of times a week in the morning and come into work a little later.”

Jose stands in front of the camera with his team. Jason on the far left was working on 2018 Model Year product during my visit. Phil (middle) is the newest member of the team, so I’m told he does a lot of paper shredding and coffee making – in between running shocks on the dyno of course!

Jose stands in front of the camera with his team. Jason on the far left was working on 2018 Model Year product during my visit. Phil (middle) is the newest member of the team, so I’m told he does a lot of paper shredding and coffee making – in between running shocks on the dyno of course!It certainly sounds like a good gig, but that passion for mountain biking isn’t just a coincidence. “When I look for people to hire, number one is character, and number two is passion for what we do”, Gonzalez tells me. “Obviously they gotta have the general tool box, but I don’t worry too much about that general tool box in the sense do they have the most suspension tuning? Because that’s what I’m here for, to help them along with those things. But if they don’t have the right character, or if they’re not passionate about it, that’s something I can’t control and I can’t change that. So for me those are really important attributes, those are the first ‘gates’ – if they don’t pass that, it doesn’t matter what else they have to offer.”

Interestingly, but perhaps unsurprisingly after what Gonzalez has told to me, it turns out that neither Jason or Phil had significant tuning experience prior to being employed at the Suspension Lab. Clearly this hasn’t been an issue however, as it doesn’t take long to identify that both staff members not only have incredible engineering knowledge, but that they also possess a very intimate understanding of mountain bike suspension. Such is the effect of being 100% immersed in a role where you’re pulling apart damper shim stacks and dyno testing day in, day out. Gonzalez goes on to tell me that his previous two staff members were also in the same boat, with no specific experience in suspension tuning prior to working in his facility. Since finishing up at the Suspension Lab however, Eli Krahenbul has since gone on as an Advanced Applications Engineer at Fox Racing Shox, while Dave Camp is now a Suspension Engineer with RockShox in Colorado Springs. Make no mistake, this is a workshop where 6 months experience is like 6 years in the world.

On the note of field testing, the decision to base the Suspension Lab in Santa Clarita was a very deliberate one. Gonzalez explains that while he could have implemented the facility straight away if he were to have established it in Wisconsin like Trek originally wanted, he didn’t think he could do what he needed to do if he were based there where it’s relatively flat and somewhat frozen solid 3 months of the year. As such, a lot of that has to do with the mountainous riding around Southern California and the access to diverse test environments within a short driving distance. This is an interesting point to make, as many bike manufacturers can often be guilty of producing bikes, geometry or suspension designs that only work for their local environment. However, a truly versatile mountain bike is one that can ride just as well on the slabby tech-climbs around Sedona, as it can descend the buffed-out flow trails around Santa Cruz. And so Gonzalez makes a point of taking prototypes to as many different trails as possible to assess how the bike may behave when subjected to varying trail surfaces.

A well-stocked machine shop means that Gonzalez can machine small parts in-house without having to wait for their manufacturing partner to send out a component. Note the rack of bikes in the background with a few blankets covering some bikes that we’re not allowed to see yet…

A well-stocked machine shop means that Gonzalez can machine small parts in-house without having to wait for their manufacturing partner to send out a component. Note the rack of bikes in the background with a few blankets covering some bikes that we’re not allowed to see yet… The Suspension Lab doesn’t just work on rear shocks for Trek mountain bikes, they’re also testing and evaluating front suspension on a regular basis too. Trek have previously adopted custom spring assemblies and damper tunes for their forks, such as the DRCV fork used on the Fuel EX and Remedy models in 2013.

The Suspension Lab doesn’t just work on rear shocks for Trek mountain bikes, they’re also testing and evaluating front suspension on a regular basis too. Trek have previously adopted custom spring assemblies and damper tunes for their forks, such as the DRCV fork used on the Fuel EX and Remedy models in 2013. White means prototype.

White means prototype.Perhaps the most important attribute that Gonzalez possesses is that he is very much in-tune with the desired ride quality that Trek’s mountain bike development team are chasing with each model. Testing prototypes in as many differing environments as possible, both in the States and abroad, is important to create a well rounded product, but Gonzalez also understands that you simply cannot produce a bike that absolutely everyone is going to love. “You need different brands, because everyone’s got a different philosophy, and you’re not always going to cater to 100% of the market with your philosophy on how you want your bike to perform”, Gonzalez admits. “You hope you cater to the majority of the market, but it’s unrealistic to think that your bikes going to be the end all answer for every rider. You know, there’s just too many different tastes and riding styles.” The key for Gonzalez then, is not to build a bike just for the pro riders, and not to build a bike just for the entry-level beginner, but to identify that enormous grey area in between, and find a particular ride quality that resonates with as many of those riders as possible. And it’s in this pursuit to reveal a bikes inherent personality where Gonzalez shows off his true skill and 20-year industry experience.

“The reason why you can’t cater to 100% of the market?” he asks me, “Is because you’ll end up with a compromised average product at that point. Because you have to stand for something to have meaning right? And if you stand for something, there’s always going to be, regardless of what you do, there’s going to be a group that doesn’t agree with that. For the product to stand out, it has to have a certain soul, a certain ride quality, certain characteristics, and that ultimately is what gives you meaning in the market, and makes you stand out.”

This is an interesting point and a potentially contentious one too. I delve a little deeper and we discover a good example of what Gonzalez is referring to, and begin discussing the lockout feature on the rear shock of most Trek dual suspension mountain bikes. With the exception of the short-travel race duallies, most Trek models have a fairly ‘soft’ lockout, that is more of a firm compression setting than a rock hard lockout. And this is potentially a deal breaker for some consumers. However, Gonzalez’ team found in both field testing and on the dyno, that adding a firm lockout feature to their rear shocks could actually cause compromised suspension performance in the open and trail settings. It wasn’t meant to, but it did. And because Trek didn’t want to compromise suspension performance, they elected for that softer lockout tune at the risk of losing sales to those riders who wanted that rock-hard lockout.

This notion was also a driver for the development of the RE:aktiv damper, which is featured on the high-end Fuel EX and Remedy models. If you’re not familiar with it, the concept of the RE:aktiv damper is to offer improved low-speed compression damping for pedalling performance, but with an incredibly fast breakaway threshold that allows the shock to absorb mid-to-large hits quickly and smoothly. Of course everyone wants pedal efficiency, but the trick is to offer it without sacrificing suspension performance.

It becomes clear throughout my factory tour that Gonzalez is largely uninterested in chasing flat-out pedal efficiency at the expense of bump response, control or traction. He brings up the term ‘balanced performance’ to describe the ride quality that he is always looking for, which in his opinion is a marriage of suspension frame design, and the shock itself, so that they are equals in the same equation. What really bugs him about some bikes on the market is that they build all of the pedal efficiency into the suspension linkage, so that you can run a shock with little to no compression damping. “The damper is such a critical part of suspension performance, that discounting what a damper can do for you I feel is a big mistake” states Gonzalez. “I don’t buy into this philosophy that you can run kinematics that basically allow you to have almost no compression damping. Compression damping is super critical for control, so you know, if you have a kinematic that doesn’t rely heavily on compression damping when you’re pedalling, what happens when you’re not pedalling? What happens when you’re descending aggressively and you’re not putting tension on the chain? And then, all of a sudden, you don’t have the control in the damper that you need for that type of scenario.”

If I had any doubt about Trek’s investment into having specialist suspension R&D facility before the tour, it is most certainly gone by the end. The level of detail that goes into characterising the suspension behaviour of each of their mountain bikes is quite staggering. Of course forks and shocks are getting better each year, and companies like Fox and RockShox are getting better at offering products that will work with a wider variety of bikes and frames on the market. The difference that separates the ‘Good’ from the ‘Really, Really Good’ is this level of custom tuning however, and according to Gonzalez, ”you’ve got to have the right suspension knowledge within your own organisation”. Even as those suspension companies progress, the reality is that those companies don’t have the necessary knowledge about your frame design. I ask Gonzalez to then summarise what it is that his team helps to offer with the end product. “Dialled is really the best way I could describe our bikes. When you get on a Trek, it’s not like you have to spend a lot of time figuring it out to get it working right. That’s because of all the work we do up front.”

Becoming somewhat overwhelmed at the level of detail and scale of the ideas being bounced around the walls of the Suspension Lab, I find myself wondering what drives people like Gonzalez to constantly search for new technologies and improvements. I’m the sort of rider that after riding a really well-rounded test bike, wonders “how are they going to improve on this – it’s so good!” But clearly I’m not from the same gene pool as Gonzalez and the innovators at Trek. “That’s our job, that’s what we do, that’s what we strive for; to continue to elevate that game” Gonzalez responds. “Regardless of how good the bike is today, it can always be better. You know, Joe V said it at one point; the perfect bike will never be made. Because there’s always things that you learn, that you can improve on, some are small, some are big.”

Ok, so that rounds out Part 1 of my Factory Tour with Trek Bikes. Keep your eyes peeled for Part Two on AMBMag.com.au, where I interview Jose Gonzalez on some of the new suspension technology on the 2016 Trek range…