The Talas Traverse: Bikepacking Kyrgyzstan

“So one thing’s for sure… there won’t be any giant egos on this trip.” Toby said wryly.

Written by Tracey Croke

“So one thing’s for sure… there won’t be any giant egos on this trip.” Toby said wryly.

The statement nicely summed up our team chat on social media about our imminent ‘trip’. We shared past experiences. We swapped tips. We each nominated ourselves the weakest link. It was reassuring to hear some self-deprecating banter slotted in between the more serious points.

With mountain adventures in Afghanistan and Ethiopia behind me, I wasn’t new to dealing with the challenges of being in the wilderness a long way from help. Still, waves of nerves ebbed and flowed. I convinced myself it was normal to feel that way, since I was about to throw myself into the unknown with people I’d never met in a country I couldn’t even pronounce.

The unknown, in this case, was the first traverse of Kyrgyzstan’s Talas Range by mountain bike – a ten-day journey that saw us riding 230 kilometres over ten oxygen-thieving passes, climbing a total of 10,000m, careering down another 11,000m, and shivering our way across 30 freezing river crossings.

I use the term “riding” loosely as time spent pushing and carrying the bikes would be determined by terrain difficult to identify on our large-scale and outdated Soviet-era maps – the only ones available of the region.

Initially, I admit that it was the word “first” that got me downloading the application from expedition organisers Secret Compass. – a specialist adventure company who takes ordinary folk like me outside comfort zones to experience the extraordinary in largely unexplored places.

I made it through the screening process along with British Photographer Toby Maudsley and Kiwi IT consultant, Gareth Humphries, who was planning a relocation to London when he figured he could fit in a world-first expedition.

Gutsy Gareth, who was already acclimatising in the Himalayas really knows how to throw caution to the wind. “I’m hiring a bike when I get there and I’ll get a couple of practice runs in,” he said declaring his rusty bike skills. “That’s brave,” I thought, while picking up spare parts at my local bike shop.

Once I learnt how to spell the country of many consonants, Google told me the Talas region sits in the north of Kyrgyzstan and is the start of Central Asia’s big mountain system, which leads into the Pamir Range and eventually the Himalayas. The area is rich in stories of Manas, a historical game-of-thrones style warrior reputed for uniting 40 clans to create the nation that exists today. He lives on like a spiritual superhero deeply entrenched in Kyrgyzstan’s national identity.

“It’s extremely remote and isolated, few people go there” explained our expedition leader Patrick Barrow, an Australian expat who owns a guesthouse in Bishkek, where we assembled ourselves and our bikes. “There are some known trekking routes, but our plan is to explore the trails shaped only by shepherds and nomads.” Either way, we were heading into bike terra incognita.

I took a cross-country dualie with me for the climbs and to appreciate a couple of kilos less on hike-the-bike stints. Downhiller Toby decided on the fun-factor of a longer travel model. Gareth managed to pick up a half decent hard-tail in Bishkek. There’s no right or wrong bike for a journey where anything can be thrown at you.

Patrick hired multilingual local guide, Anarbek, and two Kyrgyz horsemen to carry our camping gear and food – gentle giant “Umar” and fatherly figure “Kalmat” They confirmed our aim to cover 25 kilometres per day was achievable, but “complicated” and unlike anything they had heard of. The progress of this journey would not be dictated by our stamina but, quite rightly, by the welfare of their horses.

The long road ahead

From Bishkek, we spent two days driving into the Talas Range. When the tarmac disappeared, we bumped along a double track until our four-wheel-drive submitted to the rubble. We set up camp by the by the Baikyr River, below our first pass, eight kilometres south of the Uzbek Border.

A huge hot slog up Chon Kyzyl Bel pass took the whole morning of day one. “Take that,” said the Talas. Gareth’s acclimatisation proved well up to the challenge and he pushed on ahead into the thin air. Toby cursed the extra weight of his bike and camera equipment until he reached the top and got his first eyeful of Manas land.

A supernaturally lit panorama of muted tones stretched out before us. Shades of green and golden tundra rolled into jagged ice-crowned peaks. Toby clicked away like he’d hit the photography jackpot. “I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s biblical,” he said. Grinning, Patrick pointed out our trail, which snaked to the bottom of the valley.

Toby eagerly led the descent in an excited groove. Gareth and I skittered cautiously behind on the shale littered corners and Patrick pulled the perfect comedy over-the-handlebars stunt to stop us all in our tracks laughing.

At the bottom, we met a boulder-scattered carpet of lush green. It was cut with a show-stopping raging glacial river that we needed to cross at some point to reach our first planned camp spot. We set off weaving around the boulders on a faint interlace of trails whittled by nomads and their herds. Another ten kilometres would see us cooking dinner in the warm evening sun.

The trouble with large-scale soviet-era maps is that they lack the detail to calculate accurate distances or show safe river crossings. Several hours later, we found ourselves on a treacherously loose rock-strewn slope, with bikes on shoulders, still trying to cross the river in fading light.

Kalmat called time on the horses and we doubled back to safe ground. We crammed our tents atop a lone island of rock-free flat ground before dragging our grumbling bodies around the fire.

At the end of day one, our senses were already overloaded with ridiculous highs and chinstrap challenges. We unpicked the events over dinner and wiped tears of laughter until the biting cold sent us to our tents.

Ride, Eat, Sleep – Repeat.

And so the rhythm of our journey was set: Wake; pack up camp; eat; ride; curse; laugh; get lost; make life-moments; sleep. Welcome to bike-packing in the wilderness with unreliable maps where anything can happen.

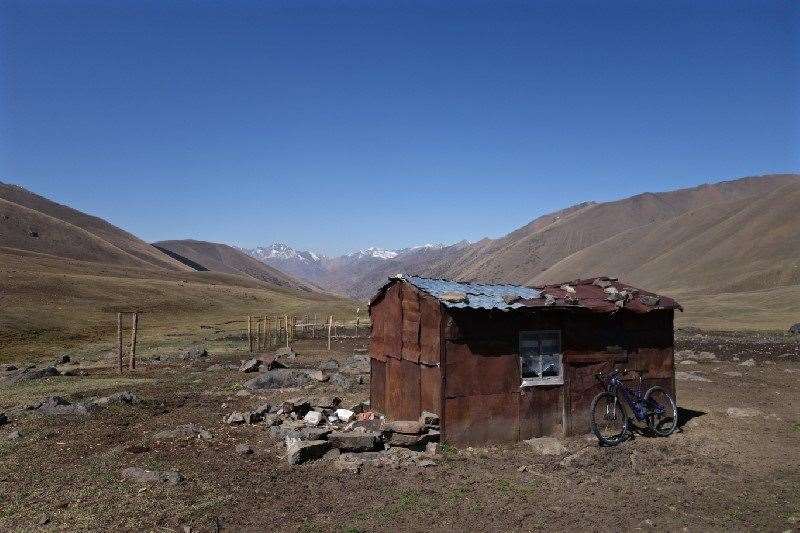

As Patrick promised, we saw only nomads and shepherds along our route. We rested in their unoccupied mountain huts – one built from 1980s era Russian newspaper plates with images still visible. “It’s cool once we leave it as we found it,” said Patrick cutting slabs of cheese and salami for lunch. Sharing is embedded in the cultural code of the mountains, whether it’s your home or last chunk of bread.

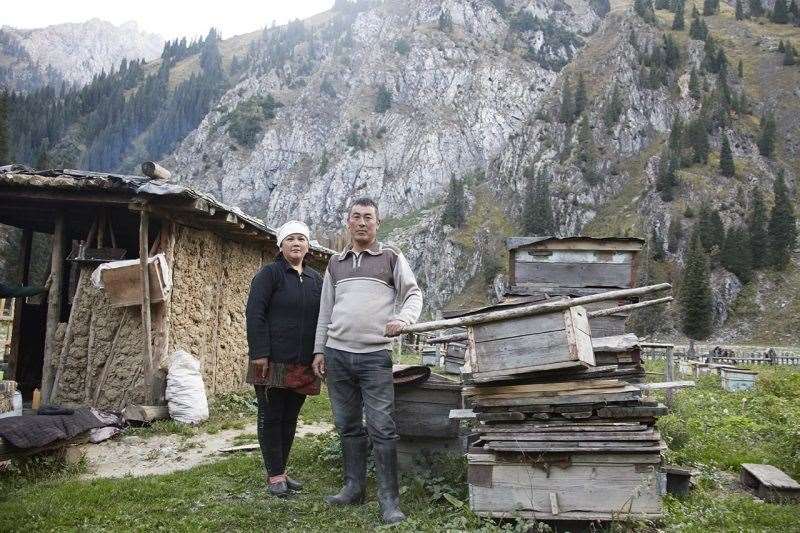

Travel is normal in nomadic life so our movements were rarely questioned. The bikes, however, caused bewilderment until the nomads had a go. That’s when the fun-penny dropped creating countless toothy grins and eureka moments. An instant bond formed. “Have some chai with us,” they said. Once a connection was made, we were treated like family. These brief encounters became a highlight of the journey.

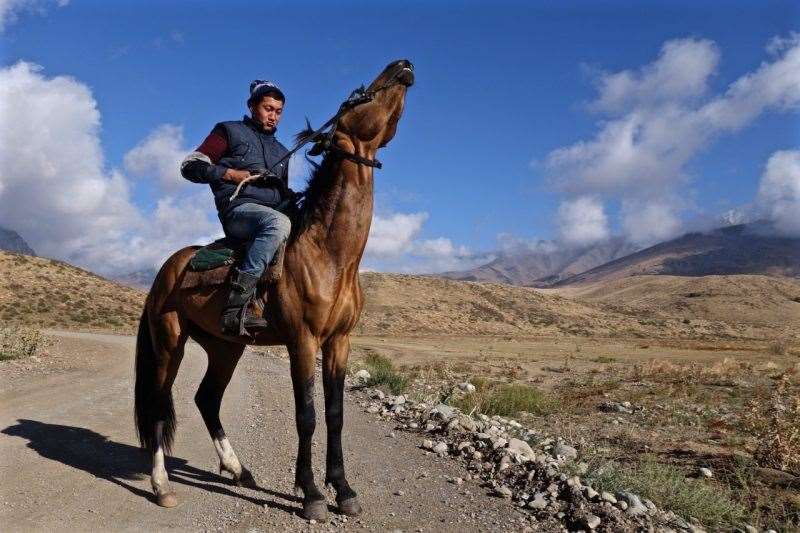

We traded laughs with passing “Dzighits” (mountain cowboys) whose skills are so absurd they can pluck a small stone from the ground at full gallop. Crucially they shared their local knowledge, which was always more accurate than our outdated maps. But not everything in the mountains was friendly.

Close to the end of the journey, the enemy of fatigue reared its ugly head. Toby was chasing a dream shot when a deviously sharp rock hidden behind a small bush sent him over the handlebars. He broke two ribs, so we set camp earlier than planned, which was fortunate for a puppy Anarbek found tied up and abandoned in a bush. Despite Toby’s increasing pain, our inner-westerners decided come-what-may she was coming with us. We named her ‘Udacha’, which means ‘luck’ in Russian.

We agreed to find Udacha a home on the way out of the mountains or back in Bishkek. With Toby strapped up and struggling with riding, we thought Udacha might slow us down even more. She had other ideas and ran alongside us almost the whole of the way. She ate, slept and cooled off in streams with us. When fatigue set in, she lifted our jaded spirits. That puppy pooped perseverance and just like a Disney movie, she became one of us – one of the team.

The next day, we couldn’t believe our luck when the baby pass of the journey (2700 metres) unexpectedly ousted us into a network of sweet trails staged before a backdrop of peaks with the apt local name “Eternal Ice Mountain.” We descended into a canyon to meet Umar and Kalmat, who had gone ahead with the horses and all our camping gear. It was a perfect morning and the day was about to get more memorable, but not for the reasons we hoped.

The floor of the canyon looked wide and rideable on the map. In reality it was a carpet of head-height thicket and thorny berry bushes. Latitudinal scratches on a tree and a bear sized flat patch right beside wasn’t the only factor in our turn back decision. A precipice forced us to find another way.

An alternative route meant slogging over another pass, which was far more appealing than spending a cold night on the mountain without food or shelter. We made it to the top with enough daylight left to marvel at the views and enjoy a smooth descent, until we suddenly came upon a worried flock of sheep hurrying towards us. Our presence on the trail sent them leaping off in all directions.

Behind the fracas, a group of frantic nomads approached on horseback. I don’t understand Kyrgyz, but in my fatigued state I imagined the raised tones plus agitated body language and ballistic sheep added up to, “get off my mountain before I shoot you.” On the bright side, I figured getting a bullet is a more fitting epitaph than being squashed by a sheep.

Patrick explained our dilemma and it turned out our animated friend (also called Anarbek) was far from angry. He was eager to stop us descending further into a dead end. “You have to go back to the top of the pass," Anarbek insisted. “There is no way through.” Patrick pointed out the trail on the map. "Forget the map. This trail is washed away. Come back with us and we'll show you the way." “Trust the local knowledge,” has been Patrick’s mantra throughout this journey. My instinct agreed.

At the top of the pass, Anarbek leapt off his horse and reassured us his son, Kojomkul, would lead us to the right trail “But first sit with us,“ he insisted. “You need meat… and have some tea.” A steel bowl brimming with cooked lamb on the bone arrived.

“Guys, share what you have,” said Patrick. Our food ran out hours ago. All we could muster was a couple of boiled sweets, a few measly peanuts and several sheepish looks. The nomads appeared far less perturbed by our pathetic gesture than we did.

I looked over at Toby holding his ribs with one hand and cradling a conked-out puppy with the other. With dusk approaching, my brain was screaming at me to get moving, but nomadic hospitality trumped my logic. Manners insisted we keep calm and carry on chomping lamb.

After our surprise dinner, we set off following Kojomkul on horseback, The dusk turned to darkness and we finally joined the illusive trail we’d been seeking all afternoon. Eventually, we stumbled into camp, made up with our worried-sick horsemen over a shot of cognac, put up flaccid tents and gratefully dragged ourselves in.

The homeward stretch

The following day, we cleared our final mammoth pass and rode down to a small yurt settlement where a jolly rosy-cheeked family greeted us with a bowl of fresh yoghurt. Udacha got a new home and I got a giant not-food-related lump in my throat that was exceptionally hard to swallow.

Finally, we unceremoniously rolled out of the mountains to a grumpy man smoking a cigarette by his van. It was a fair welcome considering we were two days overdue.

As we took our bikes apart for the long drive back to Bishkek, a unanimous feeling grew among the team. The Talas had granted our wish to ride ancient trails through jaw-dropping scenery; yet being the first to do so was the last thing on our minds.

Instead, the chatter flowed with anecdotes of nomadic hospitality and the perseverance of a puppy. Our parting gift from the mountains was beyond all our imaginations – a life-affirming journey through a pristine wilderness.

We have our unreliable maps to thank for that.

Tracey Croke is a travel journalist who likes roughty-toughty travel, off-track adventure and exploring with her bike. Her quest for a good travel story has involved venturing into post-conflict Afghanistan, being rescued by nomads and having her smalls rummaged through with the muzzle of a Kalashnikov.

Photos: Toby Maudsley and Tracey Croke

Like what you're reading? Well if you subscribe, you can get the magazine to get stories earlier – and you might even win a new Merida!