Thomas Dooley: Creating mountain bike culture

The 1990s made mountain biking.

The 1990s made mountain biking.

Up until then mountain biking had been evolving quietly in parts of the US like Crested Butte, Colorado, and in California. Suddenly, mass-produced bikes from the big brands appeared on the market, transporting the sport from the fringe to every bike shop on the planet. Innovations like suspension forks and rear shocks made off-road riding more comfortable, as did the evolution of MTB-specific gear like pedals, shoes, gloves, and clothing. With better equipment came better riders, and a race scene evolved. A culture grew around The NORBA MTB series in the US, while the UCI XC and DH World Cup series grew and grew. Kids bought mountain bike magazines along with the skate and surf mags that already littered their bedroom floors. Australian Mountain Bike magazine printed its first issue in 1991, just one of a new breed of mag that targeted an emerging fringe culture.

It was during the early ’90s that big MTB brands made their names – and made the sport. Companies like RockShox, Cannondale, Specialized and the rest all have stories behind their success – and what they had to say spoke for the riders themselves, then a tiny fringe that made up mountain biking, the misfit orphan of road cycling, skate culture, nature-lovers and adrenalin junkies that all came together in the right places and at the right moments.

Thomas Dooley – a long-time Boulder resident kickstarted his design and advertising career with RockShox.

Thomas Dooley – a long-time Boulder resident kickstarted his design and advertising career with RockShox.

One of those places was Boulder, Colorado – a town at 1700m elevation that attracts ski freaks, outdoor extremists, and fitness fanatics the world over. One young guy, Thomas Dooley – a med-school dropout and failed Olympic cross-country ski hopeful who’d spent his youth working in bike shops – set up his own design and advertising business on someone else’s money and got lucky, nailing branding and advertising for DEAN bikes, RockShox, Cannondale, and more. AMB spoke to the man who made a career capturing the spirit of what mountain biking was, and still is, all about.

He’s seen the sport evolve right from the beginning. ‘The first mountain bike I got was in ’82,’ says Dooley, ‘and I got the first production series of Specialized [the Stumpjumper – still around today]. In ’86 I travelled to Europe and rode that in Norway and Sweden and it was the first mountain bike anyone had ever seen over there. It was just a novelty then’.

Dooley spent his adolescence and early twenties working casual jobs in bike shops, but his first passion was for snow. ‘I wanted to be a cross-country ski racer. I wanted to go to the Olympics. I went to college, got a skiing scholarship in Alaska but quickly transferred to Colorado. During a World Cup in Alaska I was defeated so conclusively that I realised I was on a dead-end street. My passion had sustained me since I was 12 years old. I needed to find something else’.

He was also studying medicine, following in the footsteps of his paediatrician father, but soon realised his path lay elsewhere. After moving back home to Minnesota to finish school he hit another dead end.

‘It lasted for years but pretty soon things started to rupture, things started to break down. Part of me realised I really didn’t want to do any of this, and when I got close to going to med school I decided to quit. I didn’t have the passion for it, and it scared the living hell out of me: Skiing was over, being a doctor was over, I sold all my ski equipment or gave it away, bought a motorcycle and went back to Boulder.’

It was the mid-80s. Thomas took on a range of odd jobs, working as a removalist for ten bucks an hour, then as a secretary in the local hospital, before landing a marketing job in the bike industry working for Catalyst Communication, a company that produced annual marketing catalogues for the big brands.

‘It was wonderful people, wonderful company, amazing experience, and that’s how it all started,’ says Dooley.

As the 80s drew to a close and mountain biking emerged, another revolution, one with more far-reaching consequences for media, advertising, and publishing, was afoot.

Mac desktop computers revolutionised the way media was created, and Dooley was lucky enough to catch on early. ‘When ’88 comes along,’ he says. ‘I walk into this marketing company and I’m filling out spreadsheets and calling bike shops, making friends with people in the industry, but the thing that amazes me is graphic design. I couldn’t believe people were actually being paid to do it. And I couldn’t believe I was so naïve not to discover it sooner’.

‘When I discovered this new world and realised I was adept on the Mac, I somehow knew that if I dived into design on my own with this new tool, there was a chance that I could do something pretty amazing, and I had to try.’

‘I didn’t have time to go back to school. I learned design on my own and I learned computers on my own. The older designers weren’t so interested. They were used to typesetting, but with the digital stuff, I realised I could remove the elements that took a long time and cost so much and do it all on my own. I also had the added stress of having a child on the way with my then girlfriend. So, it was start moving or be stuck.’

‘After 12 months at Catalyst Communication I decided to start my own company. I didn’t want to do the same thing year after year and I didn’t want to work on the same stuff year after year. I found a guy that was willing to invest in me and buy my first computer and help me set up a little office and I said “I’m gonna leave”. And I just took off’.

That was 1989, right when mountain biking came of age. Dooley’s first client was Pearl Izumi. ‘They wanted to work with me because they didn’t want to do they typical catalogue and they wanted something more efficient,’ says Dooley. ‘It was tough. The technology was new and I was more savvy than most, but I had to daisy chain a bunch of hard drives together and assemble an eight-by-eight catalogue on Photoshop. It was night after night, and a lot of stress, and it was great, except we got the year wrong on the front. It was the first time I ever had a nervous breakdown. It was a good thing in the end, it worked out, and it got things started for me, but it was crazy’.

Pretty soon Dooley was put in touch with the manufacturers from a brand new titanium bike company and the super-modern DEAN bikes logo was born. Having already borrowed money from his parents, and maxed out a credit card, Dooley went even further into debt to attend a couple of international bike shows, ending up in the factories of Taiwan, where the mystique of the bike industry was well and truly lifted: Dooley saw frames on production lines. Piles and piles of high-end parts, vastly different brands made in the same factories, and realised that all those bike brands with their high-end sensibilities, euro style, or design snobbery – they all came from one place.

‘Everything that I thought was real was completely bullshit, and once I realised what the bike industry was all about I was angry. There was this rage in me, and it was my ticket. It was my freedom. When I saw what a façade it was I wanted to create some stuff that was real,’ he says.

And that’s when RockShox came along. Then owned by Boulder locals Paul and Christi Turner, who were making suspension forks in their garage.

‘Things just clicked. After Pearl Izumi and DEAN, RockShox, if I look back on it now, was the most brilliant thing that could have happened,’ says Dooley.

‘Nobody believed suspension would ever be a part of cycling, and they bad mouthed it like crazy,’ he says, ‘but I started going riding on one of the RockShox forks, some really rough rides, and I learned what the fork could do. Paul would take me up trails I’d never been on and say “don’t lean back! Lean forward! Just fucking go! Let the fork do the work!”.’

"We are the navel of the Buddha"

"We are the navel of the Buddha"

Dooley’s first job was to redesign the brand’s logo, which remains fundamentally the same to this day. ‘I was desperate for cash, and Paul gave me like $2,500 to do the logo,’ says Dooley. ‘I patterned it off [David Byrne’s 1986 film and album] True Stories because I was enamoured with David Byrne and I loved the red, the black, and the white from the album cover, and then I used a brand new font because it was brand new. It just seemed to me at the time to be the perfect logo, the thing that would be so different in the bike industry, and it took off.’

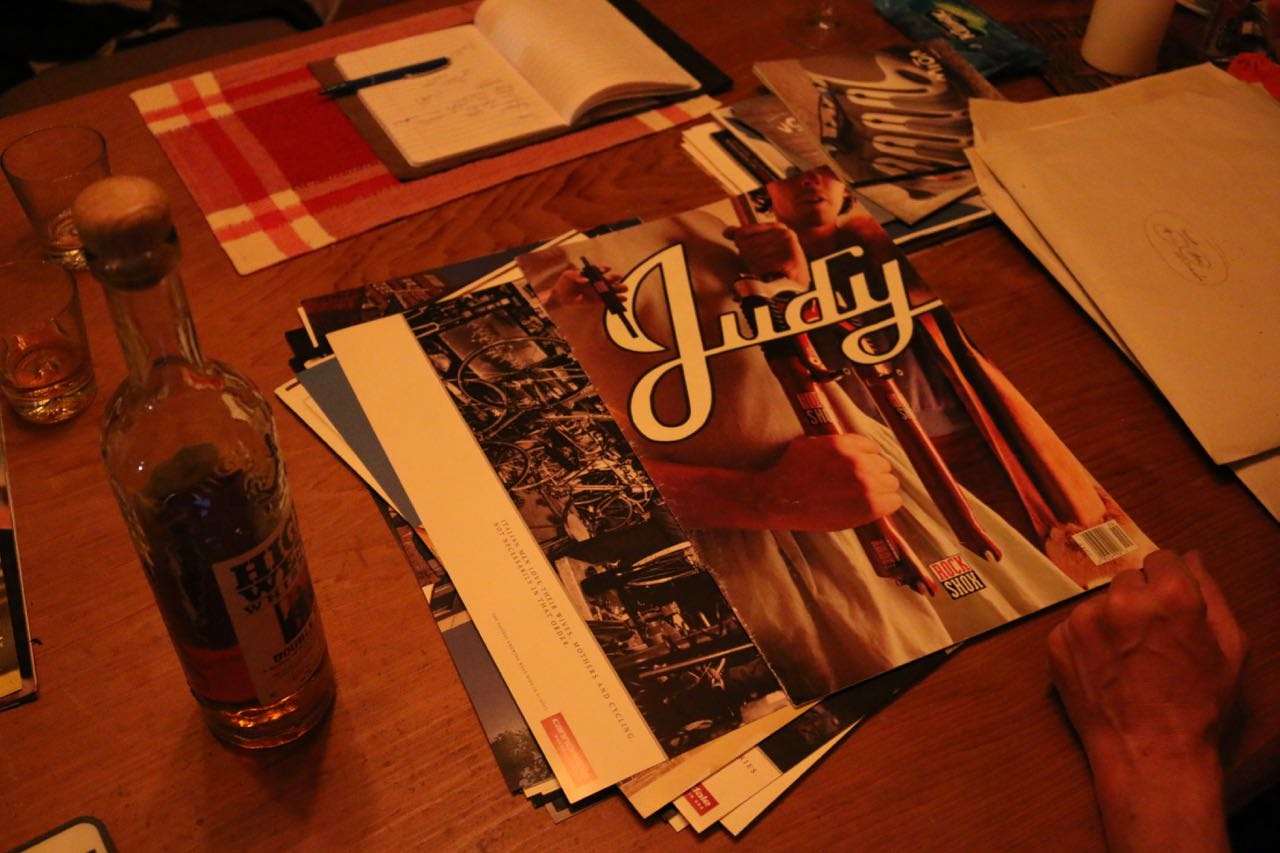

A bit later, RockShox developed a new fork. ‘Paul came up with the name Judy,’ says Dooley, ‘and so many people hated it. I mean why the fuck would you call a bike fork Judy? I loved it.’

The name provided the right inspiration.

‘It was brilliant, because when you think of Judy it was like Judy Garland. It was The Wizard of Oz. It opens up a whole new world of freedom.’

‘The catalogue we made when the Judy came out, it embodied all of that. It was mountain bike culture personified. I wanted to get across freedom and expression. It was probably the last thing that I designed completely by myself.’

1995 was approaching. Kurt Cobain had just committed suicide when Nirvana were at the height of their fame. The film Reality Bites had just achieved cult status, and Gen X ruled. The grunge aesthetic, blending authenticity, introspection, apathy, and freedom became a movement and swept RockShox along with it. Every movement needs something to define itself against: authority, the generation that came before, an ideology… For mountain biking, the antithesis was road.

‘RockShox gave us the ability to make culture,’ says Dooley. ‘We weren’t trying to do it on purpose, but we did it anyway. We were in a space in time when there was no internet and we only had print, and we were able to blast out a way of being that was brand new, and it was the antithesis of the road. Road was exclusive, road was shave your legs, road was elitist, road was “you’re never going to be as good as me”, and mountain biking was freedom. Mountain biking was going to be equality.’

‘There was this dichotomy we were trying to create that was different from the attitude of race-or-you’re-an-outcast that we saw coming from road cycling. We said: you don’t have to race, and if you do, have respect for all the other competitors, have respect for yourself, and do it for the right reasons. Race for your own courage, to survive your own insecurity.’

‘Everyone who has ever lined up on the start line knows that when you’re there you question yourself, and that’s why you’re racing. Whether you’re second, third, fourth, fifth… it’s about the fact that you participated and had the courage to do so. That’s what mountain biking was all about. The question was, are you happy? And if racing makes you happy: that’s great. If not, then do something else.’

‘We had Juli Furtado, Rishi Grewal, and Dave Wiens. Everything was going to be equal. We were going to have sport where, when you showed up, we didn’t care if you came in last, you were going to survive, because this was fucking mountain biking.’

So, what did that look like?

The 1995 RockShox Judy catalogue is a bizarre otherworldly fantasy. A side-show. A guy in a dress grips the Judy by the legs. A giant Buddha laughs out from the page, a fellow in a fur coat rides with a beaten-up, giant Gumby plush toy strapped to the back of his bike. Eight RockShox forks protrude from a murdered television. There are hula hoops. Colours. Flowers. A Cervantes quote: ‘you can we ever have too much of a good thing’. Everything came from flea markets. It was the culmination of grunge culture, skate culture, and it created something new.

‘We’re trying to say: this is enlightenment. We’re the navel of the Buddha. Kill your television with a goddamn RockShox fork and ride your bike. We’re sick of all the things we’re told to do. This is mountain biking. This is freedom.’

Right now, mountain biking seems to be looking to the past for inspiration. To its roots. We’ve all heard of the new RS-1 fork… it was named after RockShox’s first ever suspension fork, produced in 1990. There was something about that time, when the sport was new and had the opportunity to define itself as something for everybody, something made of the freedom that everybody feels when they roll through singletrack, that’s still at its heart today.

‘This is stuff that came out so long ago,’ says Dooley. ‘It’s 23 years old, but it embodies so much about the beginning of mountain biking. We weren’t playing by any rules, and we wanted people looking at this to make their own impressions’.

In the early 90s, inspiration for design came from thrift shops and antique stores, plus collections of 'things'. Dooley's wall in his shed is a monument to riding, design, art, Japanese culture – and beer.Imogen Smith

In the early 90s, inspiration for design came from thrift shops and antique stores, plus collections of 'things'. Dooley's wall in his shed is a monument to riding, design, art, Japanese culture – and beer.Imogen Smith

In the mid-1990s, Dooley was also behind the strategy that marketed the Volvo Cannondale team, bringing a team of racers from all disciplines and the idea of a factory-as-design-studio together. But what really worked, says Dooley, is the way that riders’ personalities were given pride of place in ads and marketing.

‘The thing with Volvo Cannondale was that we pulled out the personalities of the riders, people like Myles Rockwell, Brian Lopes, Tinker Juarez, Martyn Ashton, Cedric Gracia, and Missy Giove, and let them do amazing things, which I don’t think people do with their own riders now, they don’t bring more of their story out.’

‘I think that’s what’s missing today… There’s so much storytelling to be had that’s not happening, and there’s so much conceptual work that’s not happening and I think the reason these matter after all these years it that it’s beyond selling product, it’s about embodying what’s great about mountain biking. The freedom everybody feels when they get on a bike.

Dooley still rides – a lot.

Dooley still rides – a lot.

Thomas Dooley’s company, TDA Boulder, is still in operation, creating marketing campaigns for all kinds of businesses, and Dooley still competes in mountain bike events.

Thomas sees his success as a result of great partnerships. ‘There’s a ton of people to thank along the way,’ says Thomas, who thanks Leslie Bohm, Ray Keener and James Terman at Catalyst Communication for giving him his first marketing job in the bike industry and a model work environment to emulate. ‘I was driving much of the creative for the first ten years with a great bunch of folks helping, especially designer Jing Jing Tsong in the beginning,’ he says. Since 1998, Thomas has been partnered with Jonathan Schoenberg and other creatives, all of whom have helped drive TDA’s success.