Understanding your physiology and training for success

Female specific physiology information for better performance!

Words: Anna Beck Photos: Phil Gale

Ladies, can you relate to this?

The preparation had been going well, the numbers were solid and the skills were honed. The nutrition was sorted, the plan was made and you’re ready to go.

The starting gun goes off… and you started going backwards.

Have you ever had that feeling, hurting from the gun and the inability to ‘get going’? You’re hot and bothered and plagued by what seems like dehydration, despite your careful attention to event pre-hydration and watching your fluid intake mid race.

It seems, in a sport with as many variables as mountain biking, that to pin a day like that down to hormones may be a bit of a stretch but hormones can often be linked to both good and bad days on the bike.

Unpacking the menstrual cycle

The average menstrual cycle is 28 days long but can range from 21 to 35 days in healthy people, and consists of two distinct phases; day 1–14 (day one starting on the first day of your period) is called the follicular phase, and days 15–28 are called the luteal phase, with the benchmark occurrence of ovulation being the division between the two.

The early part of the follicular phase, during your period, is a low-hormone phase. In this respect, during the first 5–6 days of your cycle you are physiologically most similar to a man. At this point, mid follicular cycle, your levels of FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) increase to stimulate

ovulation. At around day 12, there is a surge in both oestrogen and LH (lutenizing hormone) to facilitate ovulation and egg release. A small dip in oestrogen takes us to the luteal phase.

Through the luteal phase, oestrogen and progesterone rise to prepare in case of pregnancy, peaking at about day 23 (or 5 days prior to your period). From here there is a decline in both hormones leading to many of the symptoms described as PMS, and starting the cycle again.

What does this mean?

Athletic performance has historically been a man’s world when it comes to studies, the fact that women have a menstrual cycle has been cited as a reason we are ‘too difficult’ to study due to ongoing fluctuations; even less studies are available on performance for women taking the oral contraceptive pill. However, it’s important to debunk the myth that having a menstrual cycle is some kind of performance curse; in fact a period has been referred to as an ‘ergogenic aid’ by researcher Dr Stacy Sims, a leader in hormones and sport[1].

The studies we do have on the menstrual cycle and athletic performance are often limited by the small number of–often recreational–athletes engaged in the study, and finding meaningful outcomes can be difficult. That being said, general trends have been found that are relatable to a large percentage of women, and apps such as FitRwomen have been developed to foster an understanding of your body and cycles as relating to performance using this data. What we do know from the small amount of studies we have, allows us to garner some insight into how the athletic body reacts to a 4-week cycle.

Week One

During the first week of your period, you’re hormonally closest to a man, this is a great time for high intensity and peak strength work. Blood sugar, heat tolerance and respiratory rate are all optimised. Exercise can actually help alleviate menstrual cramps and symptoms. You’re ready to go!

Week Two

Week two mostly mimics week one, with the exception that oestrogen surges late this week to facilitate ovulation. This is still a great time for high intensity and peak strength work, and there have been studies finding that physiology is at it’s peak for performance on day 14 of the cycle.

Week Three

Your body increases reliance upon fatty acid availability compared to earlier in the cycle, blood sugar levels start to become less reliable and you may begin to notice an increase in body temperature and reduction in immunity[2]. You may begin to feel more fatigued and less able to reach peak power numbers. The focus is on moderate-intensity and endurance.

Week Four: Recovery Week

Your body has a steep decline in hormonal levels, often believed to be the cause of premenstrual symptoms. You may experience bloating, cravings and perceived decreases in strength and power. You may struggle to recover from hard sessions; if possible it’s great to make this week coincide with a recovery week!

This example of a four week training plan is tailored to a four week menstrual cycle, training for an XCO length event (60–120mins) in the build phase, for an athlete riding 6-12hours/week: that is, much of the long distance base and strength phase is completed, moving towards a competition phase in training. Often it is at this point in a program when hormonal differences are apparent during sessions: you may struggle to hit the higher zones, and feel more fatigued or hotter or just ‘flat’ when completing intensity work.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Saunday | Total Hours |

|

Week 1 Day Off |

Zone 2 ride including VO2 Max Efforts 2x(2x4min), 3min RI with 10min between efforts, 1hr | Skill Based ride zones 2 and 3, 1hr | Mountain Bike Time Trials, 4x8min, ‘race’ simulation efforts on singletrack, 90min | Zone 1 Recovery, 1hr |

XCO Race OR 3x10min Zone 4, 90min |

Mountain Bike Ride, Zones one and two: long ride day 2:30 | 8.5 |

|

Week 2 Day Off |

Zone 2 ride including VO2 Max Efforts 2x(2x4min), 3min RI with 10min between efforts, 1hr | Skill Based ride zones 2 and 3, 1hr | Mountain Bike Time Trials, 4x8min, ‘race’ simulation efforts on singletrack, 90min | Zone 1 Recovery, 1hr |

XCO Race OR 4x10min Zone 4, 90min |

Mountain Bike Ride, Zones one and two: long ride day 3hrs | 9 |

|

Week 3 Day Off |

Zone 2 ride including VO2 Max Efforts 2x(3x4min), 3min RI with 10min between efforts, 90min | Skill Based ride zones 2 and 3, 1hr | Mountain Bike Time Trials, 4x12min, ‘race’ simulation efforts on singletrack, 90min | Zone 1 Recovery, 1hr | Mountain Bike Ride including 3x20min High Zone 3/Sub threshold efforts, 2-5min RI, 2hrs | Mountain Bike Ride, Zones one and two: long ride day 3hrs | 10 |

|

Week 4 Day Off |

Day Off | Skill Based ride zones 2 and 3, 1hr | Day Off | Easy ride in recovery zone 1hr | Mountain Bike Skills Ride, Endurance and Tempo Zones only, working on skills progression, 2hrs | Social Mountain Bike Ride | 6 |

Of course, for different disciplines (CX, Gravity, XCO and XCM) the type and duration of ‘intensity’ would vary within this program, in order to replicate the demands of each sport. This four week program is merely an example of ways to hack your physiology to get the most out of your body at different times of the month. You will notice the intensity is geared towards the first two weeks, and endurance and recovery in the last two.

[1] Sims, S. T. (2016). Roar: how to match your food and fitness to your female physiology for optimum performance, great health, and a strong, lean body for life. New York, NY: Rodale.

[2] Carpenter, A. J., & Nunneley, S. A. (1988). Endogenous hormones subtly alter womens response to heat stress. Journal of Applied Physiology, 65(5), 2313–2317. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.5.2313

Making it work for you

In the case of training for a goal event, sometimes it can be impossible to line up your cycle with the event in follicular phase for ‘peak performance’, however by using a tracker and understanding what your body does you can account for and mitigate some of the issues that can arise in the luteal phase.

For example, in the case of a warm weather event in the luteal phase you could;

• Ingest ice slushy prior to the event (there is some evidence this helps reduce core temperature).

• Take iced bottles for feed zones.

• Use an ice vest to pre-cool during warm up.

• Your body is relying heavily on exogenous carbohydrate: set a timer to eat more frequently than usual.

• Understand that you may not feel as good, but performance can be very similar to the luteal phase despite this [1].

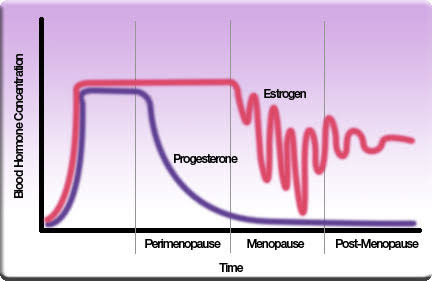

The Big Change

If there’s one things that’s studied less athletic performance in women with a normal menstrual cycle, it’s athletic performance in menopausal, and post-menopausal women.

We know that keeping active counteracts some of the disadvantages arising from hormonal changes and muscle mass loss[2]. As mentioned in the last edition, loss of muscle mass during menopause can be mitigated by incorporating strength training and also assists in maintaining bone density, which also normally begins to dive around this time.[3]

Thermoregulation can be impaired due to hormonal imbalances, resulting in what’s known as ‘hot flashes’. Some women will be severely impacted by these, others will fly through menopause barely noticing them, but some tips for managing these with training including increasing electrolyte and water intake, and once again pre-cooling when required.[4]

The takeaway

It’s important to note that some people experience quite severe menstrual cycle symptoms and others may simply breeze through with minimal problems. So it’s a great idea to track your cycle to find patterns in symptoms, feeling and performance, and for the coached athlete, speaking to your coach can really help with programming and understanding your own performance limiters.

We may not know everything about the menstrual cycle and performance but we do know that there are times where the body is primed for performance. Olympic medals have been won at every stage of the menstrual cycle, so it’s important to understand where you’re at and what that can mean to have the best chance of success month-round.

[1] Lebrun, C. M. (1993). Effect of the Different Phases of the Menstrual Cycle and Oral Contraceptives on Athletic Performance. Sports Medicine, 16(6), 400–430. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199316060-00005

[2] Bondarev, D., Laakkonen, E. K., Finni, T., Kokko, K., Kujala, U. M., Aukee, P., … Sipilä, S. (2018). Physical performance in relation to menopause status and physical activity. Menopause, 25(12), 1432–1441. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001137

[3] Muir, J. M., Ye, C., Bhandari, M., Adachi, J. D., & Thabane, L. (2013). The effect of regular physical activity on bone mineral density in post-menopausal women aged 75 and over: a retrospective analysis from the Canadian multicentre osteoporosis study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 14(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-253

[4] (2019, June 3). Female Endurance Athletes: Staying Healthy During Menopause and Beyond. Retrieved from https://www.endurancesportsnutritionist.co.uk/female-endurance-athletes-staying-healthy-menopause-beyond/