Mongolia - a steppe back in time

On the day of my arrival in Ulaanbaatar, a heavy fog shrouded Mongolia’s capital city.

On the day of my arrival in Ulaanbaatar, a heavy fog shrouded Mongolia’s capital city. It was a signal that for all I’d learned about this incredible country, there was yet much more that would be revealed as I disembarked for the 2015 edition of the Mongolia Bike Challenge.

Mongolia is a remarkable place to hold a bike race. Bordered by Russia in the North and China to its South, the country occupies a vast swath of land in the centre of the Asian continent. The number of airlines providing passage to the country remains limited to a handful of South Asian and Russian carriers. Those planes are occupied by an eclectic mix of locals, tanned backpackers and mining executives, the latter servicing the country’s 20-odd year mining boom.

A proportion of the passengers arriving from around the world in mid-to-late August came bearing mountain bikes. In its six-year history, the Mongolia Bike Challenge has done an impressive job of attracting riders from a wide variety of foreign locations. This year, a healthy dose of European riders, mostly Spanish, Belgian and Italian, were joined by Americans, Chinese, Japanese, as well as a quartet of Australians.

The melting pot nature of events like these can be hit-and-miss. Fortunately, as is more common than not with mountain bikers, it was immediately clear that this would be a great bunch of people to spend the next eight days with.

My first introductions were to Dutchman, Francesco, and effervescent Spaniard, Valentin, as we shared our transfer from the airport. We chatted about our expectations and traded a few facts we’d picked up about Mongolia. We weren’t to know it at the time, but by week’s end, I’d be trading turns with both of these guys on some of the toughest days of the race.

A day in Ulaanbaatar before a transfer to the start was spent collecting last minute supplies and exploring the metropolis. A friend of mind had described the capital as “ritzy”. Laughing it off at the time, I was surprised to discover how apt his assessment was. The impact of former Soviet occupation and the abrupt shift towards its ideological opposite is evidenced by the architecture of the city; Soviet drab meets shiny high-rise, with a dose of fluorescent lights competing for attention as night falls.

Introducing the event at a pre-race briefing its Director, Willy Mulonia, spoke of the event in wonderfully metaphorical and typically Italian terms. Days later I’d find myself comparing the realities of the event against, as Willy had put it, its “soul cleansing” nature. We were assured, however, that we were lining up for an adventure and it would most definitely live up to its title.

Best laid plans

The following day, our group of 70-odd foreigners and a handful of Mongolian riders transferred to the start, an hour outside Ulaanbaatar at the foot of a towering statue of the country’s beloved Genghis Khan.

It also marked our first night spent in a Ger. The traditionally semi-permanent shelter to Mongolia’s nomadic people is one of the most recognisable motifs from the country. That our Gers were fixed on concrete foundations, some with en suites, mattered little as we finally had the chance to admire the elaborate wood and canvas construction of their outer shells.

Last minute adjustments to bikes and final pre-race test rides were carried out with heady excitement, as those short rides also gave us our first taste of the dry Mongolian climate.

Mongolia sits atop a series of steppes, vast plateaus spanning the centre of the Asian continent. Much of the country is over 1000 metres above sea level. The impact of this elevation by itself is negligible, but when combined with incredibly dry air and omnipresent dust, gives the impression that you’re riding at significantly higher altitude. It’s so dry that what little snow falls in the country usually evaporates before it can ever melt.

In a blog entry I wrote before the day before the start I referred to a number of veterans of the race who had returned for another go. With so many people taking on the race for the first time, these individuals became a valuable source of insider knowledge. Amongst these was fellow Australian Peter Selkrig, who was generous with advice throughout the event. The 54-year-old is a recognisable face on the Australian mountain biking scene. A fierce competitor, he’d returned to Mongolia to defend his category victory of a year before.

I was particularly eager with my questioning. This was my first stage race on a mountain bike, and the longest stage race of my life. I didn’t know what to expect, but as Peter was quick to point out, that’s a good place to start regardless of how many you’ve done.

“The races are so long, anything can happen. You could get sick, you could have mechanical problem. A lot of things are out of your control. All you can do is control the things you can and hope that you stay out of trouble,” he cautioned.

Reassured, that night I went to bed with a simple plan: One day at at time.

Shellshock

Slumped on the grass at the end of stage one I was in shock.

“Everyone says the first stage is the hardest,” said Lee Rogers, the event’s communications direction and fellow competitor, as he wandered over, passing me a bottle of water.

“It just didn’t look that hard on paper,” I muttered between greedy gulps.

Earlier, Italian Nicholas Pettina had won the opening stage by 15 minutes.

The stage had covered 115km and 2,400 metres of climbing. There’s certainly races that include more of both, but like many participants I’d been so transfixed on the apparent difficulty of stages four and five – over 165km apiece – that I’d ignored the fact that other days were bound to be challenging. The stage race learning curve was starting to resemble the day’s first climb.

The altitude gain itself wasn’t that mind-blowing, it was the way it was delivered. The country we were racing through was a series of long, flat grassland sections separated by sudden and incredibly steep hills, pitching up to 30% gradient at times. My determination not to hike-a-bike had been swiftly knocked to one side by the Mongolian landscape.

Still, here we were, one stage down, six to go.

Over the following days Mongolia’s epic landscape would reveal itself. The Mongolia Bike Challenge is contained almost exclusively within Khan Khentii National Park, North East of Ulaanbaatar. The race takes place on sandy, and sometimes corrugated roads that snake like veins across the wide grass plains. The climbing continued, though rarely would it match that of the opening day’s profile.

Any sense of growing isolation as we moved away form the capital was tempered with the incredible beauty that surrounded us. We crossed bubbling streams and lush grasslands, occupied by non-plussed cattle and robust native horses. Overhead, birds of prey circled. It was these moments, surrounded by nothing but the flora and fauna of the country, that captures the essence of this race.

Riding alone towards the end of the fourth stage, I found my path blocked by an enormous herd of sheep and goats too big to ride around. The delay was a minute at most, but it was long enough for me to stop, incredulous, as I enjoyed a front row seat to the dance between nomadic herders and their flock. A moment of magic.

Facing the Challenge

By the end of stage three, Peter Selkrig’s advice couldn’t have proved more prophetic. For him, it meant assuming the lead in his category as his main rival suffered a race ending fracture to his frame. For me, the defining challenge of the week made itself apparent.

The stage finished with a gradual 30km climb which suited my style of riding. Yet, as the road rose upwards, my breathing slowly reduced to the capacity of a straw and anything over 2% gradient forced me off my bike. Thinking my race was over, but determined to finish the stage, the final 10 kilometres took an eternity as I alternated between riding and walking.

Yet, Pete’s advice cut both ways. With so many stages and so many opportunities for things to change, just do everything in your power to line up each day. The advantage of experience in stage racing boils down to an ability to adapt to the unique bubble that forms around each event. For the uninitiated, like me, it takes time to adapt to the routine of eat, ride, eat, sleep, repeat. Each element of that seemingly simple schedule takes time to get used to, takes time to optimise.

Equipped with an inhaler by the doctor, I set about eating and sleeping as best I could, resolving to be at the startline the next morning.

Stage four was dubbed the Queen stage of the race. It would cover 165 kilometres, and would be backed up by an even longer, 170-kilometre stage the following day. I wasn’t alone in my apprehension. For most, these two stages had loomed largest since we’d examined the course for the first time a year earlier.

One hundred and sixty-five kilometres is a long time to spend on a bike. On a mountain bike, especially so. Stages like this therefore get broken down further into smaller, psychologically manageable chunks. One of the things the Mongolia Bike Challenge does especially well is placing their feed stations. Usually three per stage, or four on the longest, they would appear precisely where the briefing indicated. Lugging my depleted body across the tundra, this accuracy took on an extra level of importance.

The highlight of the Queen stage was an incredibly steep king of the mountains point three quarters of the way through the stage. After gradually climbing through a grass-laden valley, we were presented with a steep ascent which wouldn’t have looked out of place in any of John Wayne’s back catalogue. Challenging though it was, the Queen stage came and went. It’s successor, however, would prove for me at least to be the toughest of the race.

At the beginning of stage five I dropped all pretence of expectation. Pre-stage chatter preached the importance of staying with the group, as the first 80km were either flat or down hill. “We’ll cover that in 2 hours,” became a common refrain.

Flat though it was, the opening hours were marked by tough roads. Corrugations traded places for soft sand. The decision to swap to the other side of the road in search of smoother surface was followed by the swift realisation that neither offered much respite. I found myself alone. I knew it would be a long day.

With the opening stanza cleared, the road tilted upwards as hill after rolling hill lined out before us. Later that day, one of the Spanish riders in the field was hilariously accurate in his description of the stage, declaring it the “Window’s stage”, referring to the ubiquitous image splashed across millions of PCs. No matter how many kilometres we ticked off that day, the landscape, as beautiful as it was, seemed never to vary.

To this point, I’d finished most stages alone. Today, however, I knew company would be critical to finishing that day. After a number of kilometres at the side of my transfer buddy Valentin, I settled in to spend the day with Francesco, and Rob, an American, with whom I’d shared accommodation over the previous few days. Together, we encouraged each other along with occasional spurts of conversation laced to break our otherwise silent conviction of reaching the finish line.

Relationships forged during competition are a funny thing. The furnace of competition, or simply a day like the one Francesco, Rob and I would spend riding together, bonds you in a remarkable way. At the end of that day I used what little Dutch I know to thank Francesco. We were both spent, physically, but more so emotionally. Yet, with over 335km under our wheels over the preceding two days, we also knew at that point that save for disaster, we were going to finish the event.

As the Mongolia Bike Challenge evolves through its seven stages the event naturally splits into two halves. Many race, battling it out for a spot on the daily podium and the reward of a high finish in General Classification. For others, the challenge rolls onwards and upwards; each stage conquered with a sense of pure satisfaction.

Heading for home

It’s rare to view a hilly individual time trial as a blessing. Even with legs screaming, the prospect of trading another long day in the saddle for a couple of hours effort made it a fun exercise, not to mention providing a long afternoon of recovery ahead of the final stage.

The finale, a 90 kilometre stage to a traditional Ger camp perched on top of a mountain, provided a glorious day’s riding. Even the presence of rain in the final hour’s racing couldn’t dampen spirits as we rode into the camp and across the finish line. It’s difficult not to feel at least a small sense of triumph, particularly when you’re escorted for the final 500 metres by armour-clad warriors on horseback.

Arriving an hour in advance of me, Nicholas Pettinà had ridden to win the stage and an emphatic overall victory. The Italian had finished a narrow runner up to Cory Wallace a year earlier in the Elite – Khan – category. At home he’s a full-time employee of the Italian Ranger service, an arrangement with the government that allows him to train and race as a professional rider with the support of a salary and job should his results ever slump.

“I am a bike rider.” he told me in a tone that required no further follow up when I asked him about his vocation a few days earlier.

The only thing more striking than Pettinà‘s dominance on the bike was his relaxed manner off it. Mongolia had had a calming effect on all of us. Surrounded by breathtaking landscapes, and free from the frenetic pace of life back home, perhaps Willy had been right. Beneath the weariness of seven days racing, my mind was clear.

Aussies on Tour

The Australians racing the Mongolia Bike Challenge had a successful time, with Peter Selkrig and Philip Orr winning two of the five categories on offer.

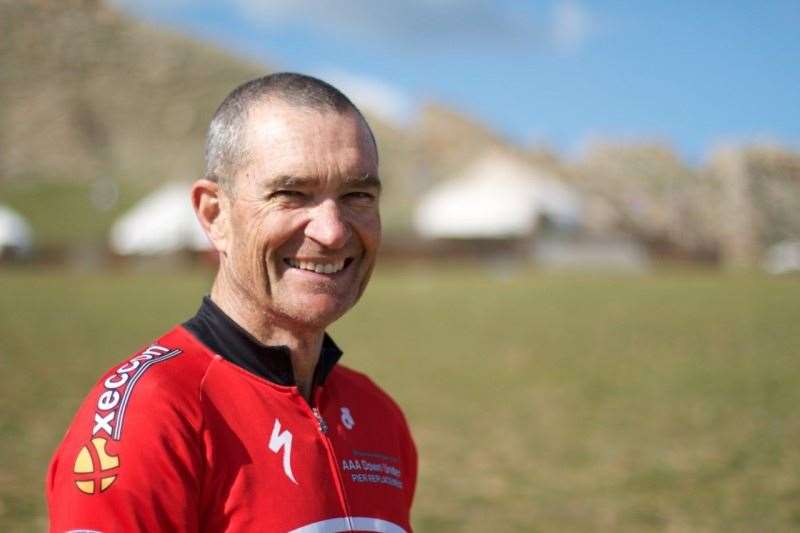

Peter Selkrig

Pete returned to the Mongolia Bike Challenge after his first participation in 2014, successfully defending his victory in the Veterans category. The race provided a solid week’s racing prior to his arrival in Denmark to represent Australia in the Masters World Championships a week later.

Pete Selkrigg. Photo: Richie Tyler

Pete Selkrigg. Photo: Richie TylerPhilip Orr

Racing the event for the first time, Phil finished sixth overall on his way to victory in the Master 1 Category. The Ballarat local proved an incredibly strong member of the small group that led the race each day, and was a regular at the daily podium presentations.

Phil Orr. Photo: Richie Tyler

Phil Orr. Photo: Richie TylerMatthew Turner

A fellow first timer and Ballarat boy, Matt enjoyed a contrasting race. What began with a glut of punctures would finish with a stage podium on the longest stage of the race as he rode stronger and stronger each day.

Matt Turner. Photo: Richie Tyler

Matt Turner. Photo: Richie TylerPeter Lister

Although not an official participant, Pete’s role as an on-bike cameraman for Japanese television station NHK gave him a front row seat to the action at the front of the race. The action and crashes he captured on GoPro will be broadcast as part of a documentary of the race due for release early in 2016.

Pete Lister. Photo: Richie Tyler

Pete Lister. Photo: Richie TylerMy bike at the Mongolia Bike Challenge

I rode a Whyte 29-C equipped with Shimano’s XTR M9000. There were points rattling over corrugations and river rocks that I was envious of those riding dual-suspension bikes, but on balance the sheer volume of smoother surfaces and climbing meant that a light hardtail served me well. If you plan to come to race MBC bring a hardtail, if you plan to come for the experience, bring a dually with a wide gear range.

Good tyres are a necessity. Reinforced sidewalls will be an asset – I rolled Maxxis Ardent Race and Ikon EXO tyres and went puncture-free all week. Definitely take a handful of spare tubes with you.

The race is attended by mechanics who offer pre-paid service packages. Opting for these will take a way a lot of bike-related stress. There’s various levels available, but they’ll take your bike at the end of each stage, attend to any issues and have it ready for you for the next days stage. If you opt not to employ the services of the mechanical team, they do carry spare parts which you can pay for with a credit card. Be polite, with so many bikes to service each day, they’re some of the busiest people at the race.

The resourcefulness of the mechanics is worth mentioning. In lieu of the required part, a fairly serious bottom bracket issue was resolved using a carefully crafted beer can!

MONGOLIA FOR 2016

Organisers have announced planned changes for the 2016 edition of the race and the race will be reduced by one stage and that the average length of stages will be reduced. Race Director Willy Mulonia told AMB that the individual time trial will remain a part of the race and that for the first time in its history the race will start from the Mongolian capital, Ulaanbataar.

At time of writing the race had a limited number of early-bird entries available via their website –mongoliabikechallenge.com